simulation and games

We will think about interface metaphors and feedback systems, and talk about some of the history of cybernetics.

The would-be model maker is now in the extremely common situation of facing some incompletely defined ‘system,’ that he proposes to study through a study of ‘its variables’.’ Then comes the problem: of the infinity of variables available in this universe, which subset shall he take? What methods can he use for selecting the correct subset? Ross Ashby

lecture: simulation and games

Today’s lecture will be pretty short! I’ll show some systems, we’ll talk through a few concepts, then I’ll demo the tool we’re going to look at this week. Like last week, the tool we’re going to be using is designed by Nicky Case: this one examines feedback systems, rather than cellular automata.

a brief history cybernetics

Many of the ideas that we’re exploring with simulation come from a 20th century movement called ‘Cybernetics’. Stemming from the greek word Kubernetes, or ‘steersman’ (yes, there’s also a cloud computing application called Kubernetes but the greeks got there first, and cybernetics got there second), cybernetics in its inception was concerned with the idea of control systems and information.

Norbert Wiener coined the term working on automatic anti-aircraft guns during the second world war. He noticed that soldiers firing the guns would not fire directly at their targets, but slightly ahead, to compensate for the anticipated distance that the craft would travel between firing the shell, and the shell arriving.

Wiener gave the movement a life of its own, and its adherents quickly found uses for ideas of control systems and feedback, first in electronics and in the early days of computation, but also in architecture, management, biology and psychology.

feedback

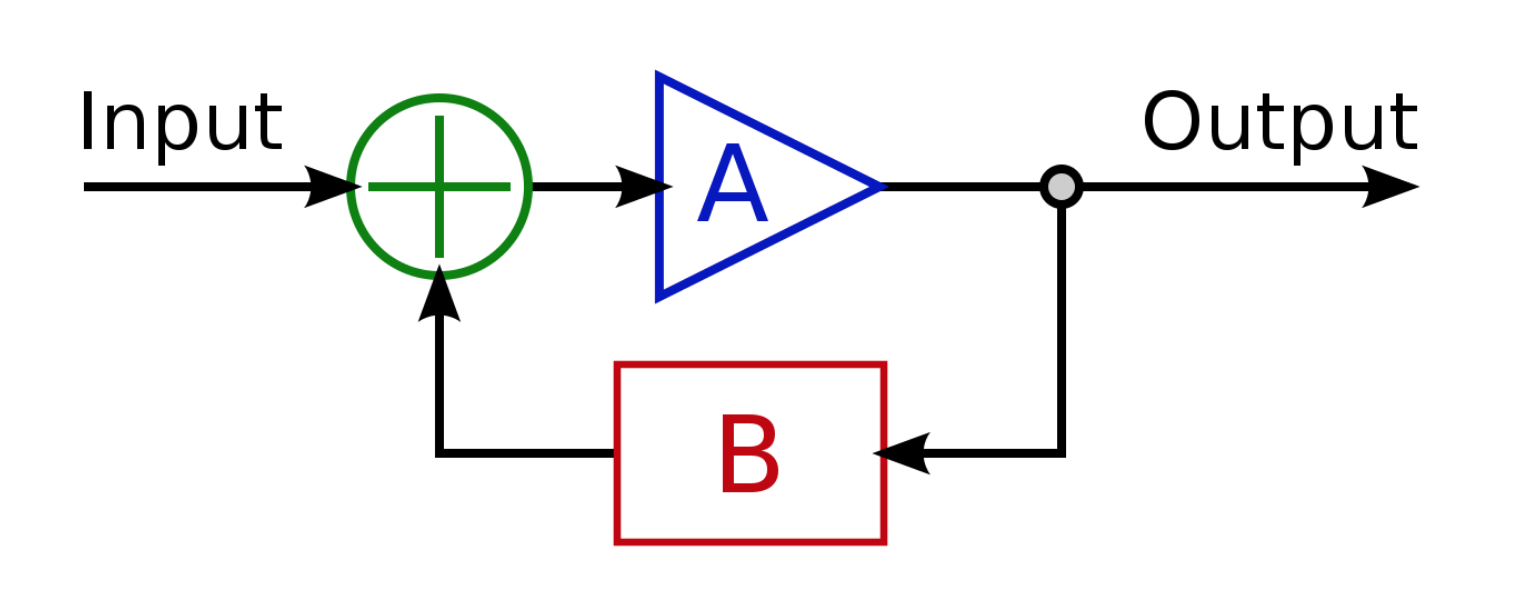

Perhaps the most central concept to cybernetics is that of positive and negative feedback. Consider the following feedback model:

This model shows us a snapshot of a whole system. We have some effect A (this), and some response B, based on the output of the system. The results of the response, and the original input, combine to produce a ‘closed loop system’.

An example of positive feedback in this system would be one where, in response to an increase in the input to A, the output also causes B to increase. Consider for example, that A is ‘cattle running’, and B is ‘panic in a herd of cattle’. As the number of cattle running increases, so does panic in a herd. But, as panic increases, so does the number of cattle running. Soon, the cows are out of control!

An example of negative feedback would be something like your body temperature. As the temperature in your body increases (A), your internal regulatory system (B) kicks in and you start to sweat. The sweat evaporates from your skin, causing you to cool down: eventually, you’ll be cool enough to stop sweating, and the regulation turns off.

How could we regulate the cows? This diagram gives us an idea of where to intervene. If we could detect when cows start running, we could implement some kind of panic-reduction mechanism (a friendly sheep? cow sedatives?) before we get to a stampede, causing negative feedback. Calm returns to the cows.

causal loop diagrams

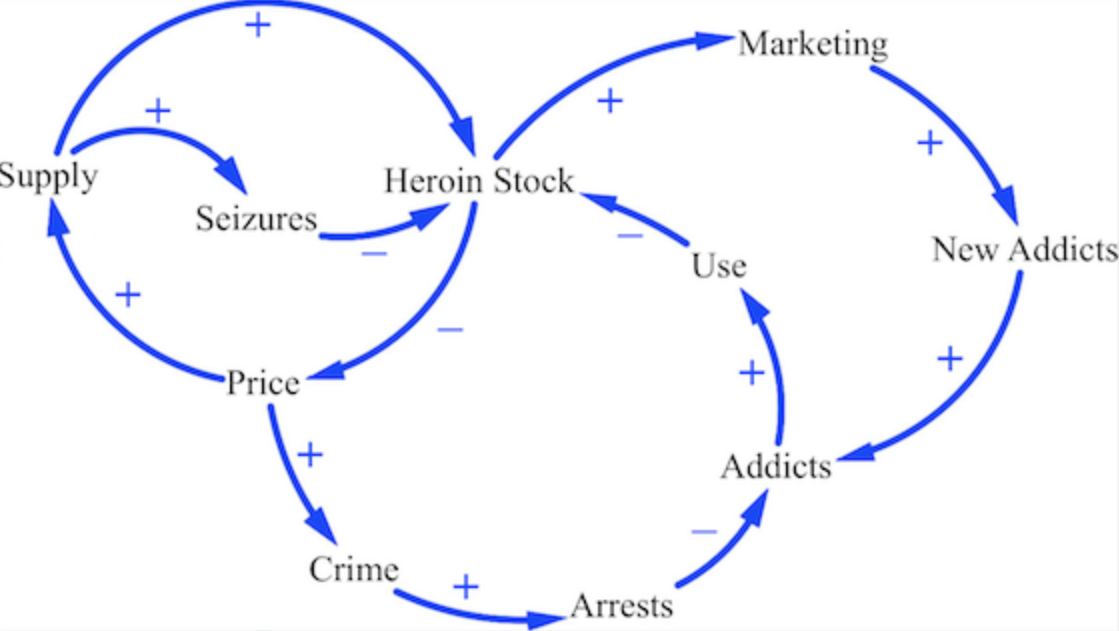

We can extend these feedback diagrams using a form of representation called a causal loop diagram, which we’ll also be making today.

The following example (which Nicky Case also talks about) is a causal loop diagram showing the difficulties of fighting the heroin trade. This diagram is of course, a smaller representation of a much larger and more complex system, but it addresses some of the key dynamics in how the system operates.

Intuitively, one might increase seizures of the drug, which will reduce the heroin stock. However, we can see that this will increase the price, which will incentivise not only the supply chains (thus driving stock back up), but also crime associated with it’s acquisition. That in turn might drive up arrests, which could drive down addiction, which could drive down use… which is good, but then increases marketing efforts, which increases use again.

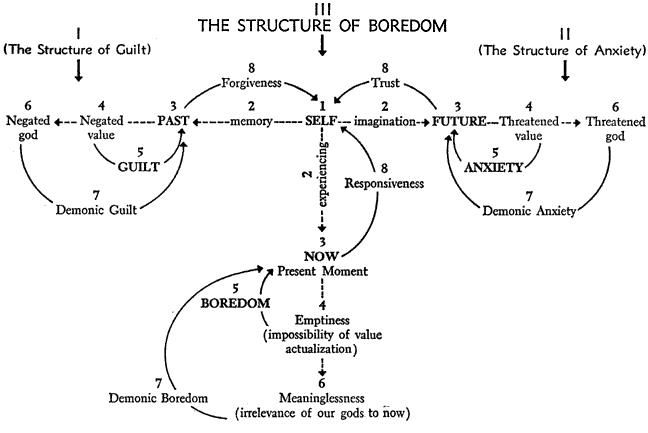

For a less harrowing example, consider this diagram of boredom, showing transformations between different emotional states.

[loopy](https://ncase.me/loopy/)

Or this dynamic product adoption model:

Or these diagrams of climate change.

explorable explanations

As we’ve already talked about, simulations can be useful tools for otherwise complex, large, and hard-to-conceptualise systems. One person who talks a lot about this idea is Bret Victor, who coined the term explorable explanations (he also designed the iPad, and is working on a project called Dynamicland, which we’ll touch on later in this class). An ‘explorable explanation’ is a reactive document that allows a reader to play with premises and assumptions, exploring different possibilities and seeing the consequences of their actions.

For example, Victor’s prototype Ten Brighter Ideas includes these simulations in an interactive document about conservation and public action.

Nicky Case has started a collection of different ‘explorable explanations’ people have made, and catalogues them on this website. Examples include:

worlding

Does every graphic design create a parallel world? – Laurel Schwulst

Every website you create is its own world. What I mean by this is that, all websites have some kind of world-view to share, and part of this assignment is developing ideas for how you might communicate that. Computers, as devices, are particularly ripe for the kind of systems-imagination that allows this kind of communication. Think about websites that effectively communicate a worldview. They don’t necessarily have to be complex, realistic or visually rich, but instead exploit their medium to tell a story. Laurel Schwulst’s teaching website Very Interactive is a nice example: it uses very simple changes to the interface to create very different effects.

Some systems reveal their complexity over time. Frank Lantz’s game Universal Paperclips is one of these, starting extremely simply (you are tasked with making and selling one paperclip at a time) to consuming the entire planet in the quest to produce paperclips.

Pippin Barr’s Burnt Matches is a text-based game based on a film about a decommissioned nuclear power station. He uses small flickers and pauses to create a surprising amount of tension, with few other visual cues.

Both of these games come with no instructions, menus or tutorials: you learn how to navigate the world by playing it.

Ian Cheng’s project Emissaries Guide to Worlding that we looked at last week is a 0-player game. In his book by the same name, Cheng describes his (and our) roles in communicating worlds as that of ‘emissaries’ – representatives from another universe tasked with communicating the dynamics of the world to others.

exploring systems through inferface metaphors

Simualted desktop/computer environments can be cheap and interesting ways to create new worlds, as they all encode certain assumptions about a medium, which can then be perturbed in different ways.

For example, Frank Lantz’s Universal Paperclips game is so effective, in part, becuase of its simplicity. By using components that have expected behaviours and simulating a piece of software (rather than a game, per se), he creates a representation of a world as it might look like to the AI that you are playing at being.

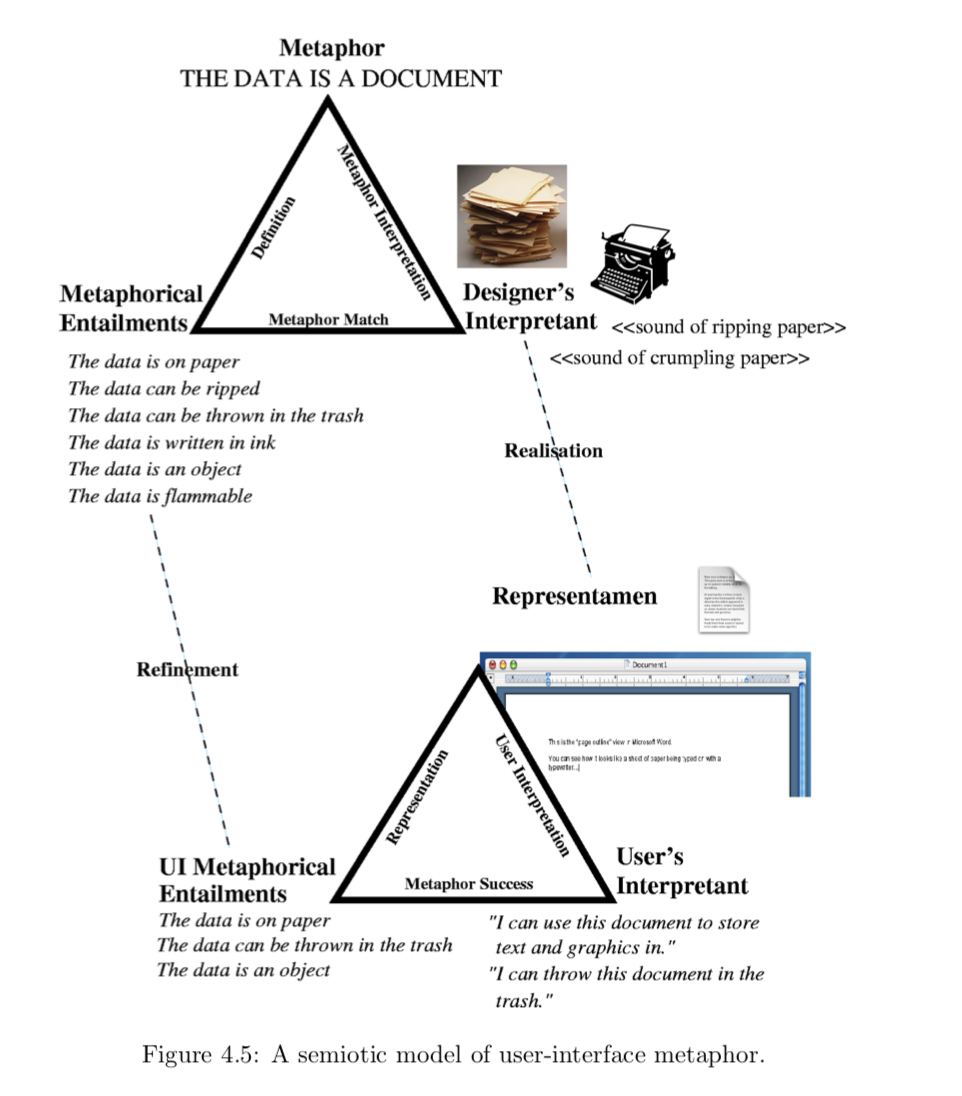

Game designer Pippin Barr uses this diagram to represent the system of metaphor involved in interface design. In it, he explores the model of the word processor in terms of mental models both Users and Designers have of the medium: we assume that one can store text in a document that feels similar to a surface we would write on.

His simulation it’s as if you were doing work gets at some of these themes, placing you in a simulated office environment. Artist Ryan Kuo’s project family maker uses the OSX interface to explore family dynamics, (mis)using familiar windows and tools to unsettle.

assignment

due 04/19

Write a proposal for your final project. This proposal might be around the system you were exploring in today’s class, or something totally different. If you need a reminder of the criteria or requirements for the final project, please see here, and email me if anything’s unclear.

This week, please write this proposal up on your site, to include the following:

- a detailed description of what you plan to make

- using either Loopy, the Simulating tool from last week’s class, or hand drawing, include a sketch of the system you plan to model

- a diagram of how different components of your system will fit together: how will someone interact with it? What APIs will you use?

Be prepared to spend 3 minutes at the start of next class presenting what you’re thinking about!

As your readings for this week, please spend at least 10 minutes playing one of the games from the short list below, and at least 20 minutes playing one of the longer games (NB: if you choose dwarf fortress, set aside at least an hour, 20min and you won’t get past the first set of menus… DF is great but it is not short). In your responses, please address the following questions:

- what are the similarities between the two games you played? What are the differences?

- what is the system being modelled in these games? What effects (if any) are you having on this system by playing?

- what parts of the system can’t you control? Are there parts of this game that are frustrating or energising?

- does the game try to make a point about the system that it’s modelling? (think about the Ian Bogost reading from last week)

A general reading for this project, one you can choose to look at this week or next, is Nicky Case’s how to simulate the universe in 134 easy steps. It’s short, and a nice framework for thinking about the act of worlding, particularly with reguards to simulation. Also really worth reading is Francis Tseng’s write-up of the Humans of Simulated New York project, a systems simulator that allows players to model different speculative outcomes for a city.

short

it’s as if you were doing work

epitaph

nova alea

art game

Burnt Matches

long

the founder

universal paperclips

simCity ($) (i play the 2000 version free in an emulator)

dwarf fortress

in class assignment

Use Nicky Case’s Loopy tool to construct a model of the system that you recorded for your assignment.