what's the internet??

“While many have debated the origins of the Internet, it’s clear that in many ways it was built to withstand nuclear attack. The Net was designed as a solution to the vulnerability of the military’s centralized system of command and control during the late 1950’s and beyond. For, the argument goes, if there are no central command centers, then there can be no central targets and overall damage is reduced.” Alex Galloway, Protocol, 2001

The myth persists that the Net was built to withstand the blast of an atomic bomb. But that was the military-run Arpanet of the 1970s, not the corporate-run Internet of today. “What’s basically wrong is we are centralized,” explains Dr. Peter Salus, Internet historian and author of Casting the Net. “We have violated the constraints that the Department of Defense had in 1967.” Wired in 1997

So i sent you a http request… but where did it go?? welcome to the weird and wonderful world of the internet protocol. in this class we’ll unpeel some layers of abstraction that keep the internet looking like it’s working great all the time (it’s actually a big big mess), learn about media archaeology and network forensics.

reading discussion

How do you imagine the internet?

Do you think governments should be able to intercept phone communications?

How might the internet be different if it wasn’t developed by the military?

Do you think companies like Amazon should be responsible for what happens to their products after they get used?

lecture: the internet is just other peoples’ computers

some ideas

a series of tubes

whatever this is

what shape is the internet?

an incredibly 90s animation of how the internet works

precursors

We talked already about the origins of HTTP at CERN, with Tim Berners-Lee. However, precursors for the internet as we know it go back a long way before that. HTTP sits on top of a vast set of infrastructure that allowed messages to be sent in the first place, derived from the military protocol ARPANET network map

The SRI Packet Radio Van, was involved in the first TCP/IP transmission (1977). This was used to test a connection between wireless packet radio, and the wired ARPANET network -> an interconnection between dissimilar networks.

It was the clear differences between the wire-based ARPANET and the radio-based packet radio (and eventually satellite networks) that led Kahn, then heading the networking efforts at ARPA, and Cerf at Stanford University, to design the first end-to-end protocol that would span dissimilar packet networks.

Ironically, the highest-bandwidth data transfer for most instances remains driving a truck full of hard drives from place to place.

Internet Protocol suite

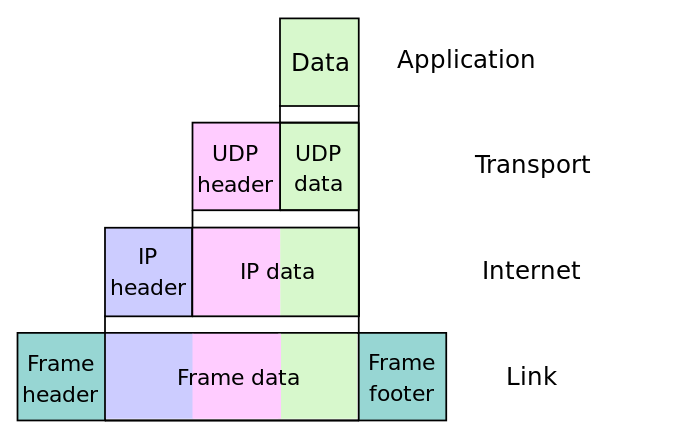

The stucture of the internet is wildly complex, and operates on a number of different levels. For example, the correct functioning of an undersea cable, a router, and a HTTP request might all be critical to a website working as expected, but it’s clear that how each of these are meant to work (and work together) occupy very different areas of concern.

These ‘areas’ are typically formalised into a layered diagram or ‘stack’, where each sucessive layer works with an abstraction of the layer that preceded it. Each layer solves a different ‘problem’, and relies on the other layers working correctly. This gives an overview of what each different part of the ‘stack’ is meant to be doing, and how it relates to the one beneath it.

The layers are structured so that the representation of data in each is standardised. This means that what’s underneath could be replaced by something totally different, and the stuff on top would keep working the same. This is what allows us to switch so easily between working on WiFi vs a LAN vs a cellular network, for example: all of these are different kinds of link layer, but to the stuff on top (the URLs we speak to, the HTTP requests we make) everything still looks the same.

What’s cool is this also works for people: at every layer, the stuff below just looks like a black box: you put an email in, you get an email out -> send a packet in, get a packet out. It’s the same for the stuff above, too: the wires you send an image down don’t know any more about the image than you do about being a big piece of copper in the ground: all the business of making sure information arrives in one piece is dealt with further up.

What is a protocol? In it’s simplest sense, a protocol is simply a formalised way of doing things: a set of rules, arrangements and agreements that define a set of expected behaviours. It is protocols . The thing about protocols is that they’re simultaneously very dull, and wildly interesting, as they define a huge amount of how we communicate with one another. Thing is, most of what makes the internet work is not wires or computers or 5G or high-tech, but bureacracy. Internet people like proposing joke protocols in very formal language, like this one for controlling coffee pots, or doing IP traffic with pidgeons. (“IPoAC has been successfully implemented, but for only nine packets of data, with a packet loss ratio of 55% (due to operator error),and a response time ranging from 3,000 seconds (≈54 minutes) to over 6,000 seconds (≈1.77 hours).”)

There’s actually a lot of different protocol suites, all with slightly different perspectives on how everything connects together. The other major one are the OSI protocols (‘open systems interconnect’) which also describe how things like images and ASCII get rendered on the screen. The ‘internet protocols’ are actually a fairly small subset of how all computers can be connected together.

-

application layer

This layer sends and receives data for particular applications. The HTTP requests you made this week took place on the application layer. This is the layer where you browse websites (HTTP), send emails (SMTP), and where website domain names are resolved to IP addresses (DNS). Networked processes take place via ports – we’ll talk about these in depth next week (servers!), but they’re a way of sorting out which application data should go to. When your computer is connected to the internet, it’s listening for email traffic (SMTP) on one ‘port’ (port 25), and HTTP traffic on another (port 80). -

transport layer

The transport layer is responsible for taking in data at one end of the network, and ensuring it gets to the other side in one piece. It defines host-to-host (rather than node-to-node communications) TCP stands for ‘transmission control protocol’, and UDP stands for Universal Datagram Protocol. TCP dates back to the 1970’s. TCP ensures that packets of data are delivered without error, and in the right order. This can be really important! When you send an image, for example, it’s normally far too big to get sent across a network all at once. Instead, you need to break it down into small chunks (packets) and send the chunks one by one. How do we make sure they all arrive in the right order? TCP sets up an end-to-end connection between the communicating computers, also checking for errors and missing packets, and re-requesting them if they don’t arrive. -

internet layer

This is the layer that routes different packets across networks. The transport layer above defines the start and end-point of communication, but the packets sent from one computer to another might need to make many ‘hops’ in order to get to their destination. Importantly, the Internet Protocol does not provide reliable transmission of packets. The job of TCP is to make this all seem reliable, by compensating for packets that were dropped, or arrived in the wrong order. This is why TCP/IP is often said to be the backbone of the network. -

link layer

The link layer is the physical and logical connection between nodes in a network. For example, protocols for how data gets sent via WiFi or Ethernet exist on this layer. This layer is all about how we get from one node to another: here a node could be a computer, or a router, a phone or a cell tower. These protocols don’t care where the data goes afterward, and are instead concerned with how to get it to the next ‘step’ specified in the packet header that got written by the internet layer.

At each successive layer of the stack, some more information gets added to the data you’re already sending. Why is this? As we go down the stack, we’re getting closer and closer to communicating our message by sending some ones and zeroes down a wire. When we get there, we’ll need a lot of other pieces of information: like, where the ones and zeroes are headed? Who are they for? Which wire should they be sent down? What is their return address? How can I check these are the right ones and zeroes?

Instructions get more detailed as we go down. TCP doesn’t care about the next node the packet is going to, just what comes out the other end.

physical layer

The ‘physical layer’ isn’t explicitly part of the Internet Protocol suite (though it does get described by OSI), but it’s worth talking about here, and featured some in your readings too. This is the layer of cables, lasers and radio waves, where data gets transmitted as ones and zeroes, rather than packets, frames or requests. Every single communication on the internet passes through this layer, as does everything you do with your computer.

Transatlantic cables have been around for a long time: the print ‘the laying of the cable’ commemorates the completion of the first transatlantic telegraph cable, between Newfoundland and Ireland, in 1858. This reduced the communication time between the US and Europe from 10 days, to a couple of minutes.

The physical layer can be very fragile! Like when a Georgian woman accidentally cut off the internet for Armenia, or how sharks remain a huge threat to global connectivity.

internet and environment

As you read in Everest Pipkin’s piece about data centers, the internet uses a huge amount of energy to run the way it does. A couple of projects that engage this in an interesting way are:

DEFOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOREST

low tech magazine

One of the biggest controversies in contemporary computer manufacturing (alongisde the use of exploitative labour in factories producing these products) is the minerals used to produce them. These are linked to long histories of extractive colonialism, such as the Victorian extraction of a tropical sap called gutta percha from Malaysia. Contemporary examples of this are ‘conflict minerals’ such as tantalum and coltan, which are extracted under terrible conditions in the DRC, and have been fuelling local conflicts there for decades. The production of lithium (for Lithium-ion) batteries has also been the subject of recent controversy, as the surge in battery production (esp with the growth of electric car companies like Tesla) is using up worldwide Lithium stocks very rapidly.

wireless networking

Wireless networking is one of the weirder ends of physical layer communications, as it relies on a very finite resource: the electromagnetic spectrum. The FCC spectrum defines, but this kind of deliniation of, well, physics can cause some really weird stuff to happen, like the problem with 5G where it interferes with measurements reliant on the resonant frequency of water molecules

“You can’t just tell water molecules to change the channel, or use another frequency.” Jordan Gerth, University of Winsconsin-Madison

There’s also a bunch of weird projects people have done around detecting wireless networks:

wardriving warchalking

flagellum machinam video

mapping it out

The internet is, well, really hard to map (it’s just big). The last time someone actually managed to map all of the internet was in the 1990s – since then it’s got really really hard:

map

critical atlas of the internet

submarine cable map timelapse

traceroute weird routes singapore->bangalore

packet sniffing

Packet sniffing is a fun way to see things that are happening on your network, but it’s one to be careful with too! In general, these tools are used mostly by network administrators debugging issues with their network, though they can be used to do some sneaky stuff too…

wireshark

nmap

spoofing

nsa surveillance Edward Snowden

julian oliver

stealth cell tower PRISM transmediale debacle

data pools skylift

we talk about the internet, but there are many internets

borders choke points ‘enemies of the internet’

chinternet the ‘great firewall’ blind spot bullet time

the Egyptian “killswitch”

runet

uk ‘default filtering’

tor autonomy cube

local internet

NYC Mesh

piratebox

internet connectivity by motorcycle

in class exercise

Sending packets. We’ll emulate an internet network together over physical space, decomposing an image into packets and routing it over a network.

Rules:

- all the packets are transmitted face-down with header information on the top and the data on the bottom.

- without TCP, packets must be transmitted in the order they came in

- routers are trying to do the job as fast as possible, and don’t care about the order of the data.

- unlabelled packets get ‘dropped’ by the network if you try and pass them. packet loss can only be resolved by TCP, or by reloading the page.

Exercises:

-

ping: send a packet across the network. If the receiving computer is on and awake, send back a packet with ‘200’, also across the network.

-

changing network topology, now a choice of routers: re-arrange the network so that there’s a choice of routers, and try the ping task again.

-

images without TCP:

Computer 1 makes a request for an image from computer 2, perhaps it wants to see this picture of a frog. First of all, a GET request has to be made. After that, the image must be returned. However! The image doesn’t all come in one piece -

image with TCP:

Now we’re allowed to use TCP to control the packet transmission. The TCP clients sit on the ports of the computer, and when a request comes through they set up an agreement with each other about how the data should be ordered. The TCP client adds information to the packet headers, to allow the TCP on the other end to decode it, and re-arrange the pieces in order.

rules for routers:

your limit is bandwidth — how many packets you can pick up in each hand (your limit is 2). you have no idea what order they’re meant to be in, and you don’t care — all you care about is where they’re meant to go. you have to write the ‘address’ of each packet in the header. You’re trying to pass the packet to whichever router will be able to handle the information fastest.

you need to change the headers in each packet to decide where it should be going next. this isn’t the end address, but the intermediate step: instructions for the next router.

rules for tcp:

you’re trying to make sure the packets are in the right order every time. Initially this involves setting up communication, and labelling the packets to make sure they appear in the right order.

rules for computers:

you send and receive the data through your HTTP port. It’s up to you to initiate protocols, and you can choose to ‘reload’ a page if you don’t get what you expect.

assignment

due 03/01

Using some of the tools and techniques we’ve discussed in class, discover something about your own local internet system.

do your own media archaeology/forensics

use the tools we have (or find some other ones)

You don’t need to write any code for this week’s homework (though you can if you like!). This is a great opportunity to try a technology you’re curious about, or go on an adventure. Documentation is really important this week, and should be the bulk of what you produce!

Precaution: some of the tools we’ve looked at today are powerful, and some uses of them are of shady legality. Don’t (for example) try and hack into someone else’s computer unless you have their permission.

examples:

- when connecting to the wifi in different places, record how many other devices are also connected to the networks.

- look at where your packets are routed at different times of day

- go on a journey to your local data center (if you tell them it’s for a class in advance, they might let you in!)

- have a look through Networks of New York and go hunting for similar features in your neighbourhood

- join the NYC Mesh! (if you’re currently paying for wifi this will also save you $$)

You’re also welcome to spend the week diving deeper into one of the things we’ve discussed in class, or in the readings. Be sure to write thorough notes!

Before next week (if you haven’t already), please install NodeJS and the Node Package Manager (npm).

Ideas+Resources:

Neal Stephenson Mother Earth Mother Board

Randall Monroe Google’s Data Centers on Punch Cards

Ingrid Burrington Networks of New York

NYC Internet Master Plan

Museum of Wifi

Trevor Paglen Eagle Eye Photo Contest

NYC Mesh

networks.land

reading

Ethan Zuckerman, The Cute Cat Theory of Digital Activism

Paul Ford, i had a couple of drinks and woke up with 1000 nerds